A State Policy Brief from the National University-Based Collaborative on Justice-Involved Women & Children (JIWC)

December 2023

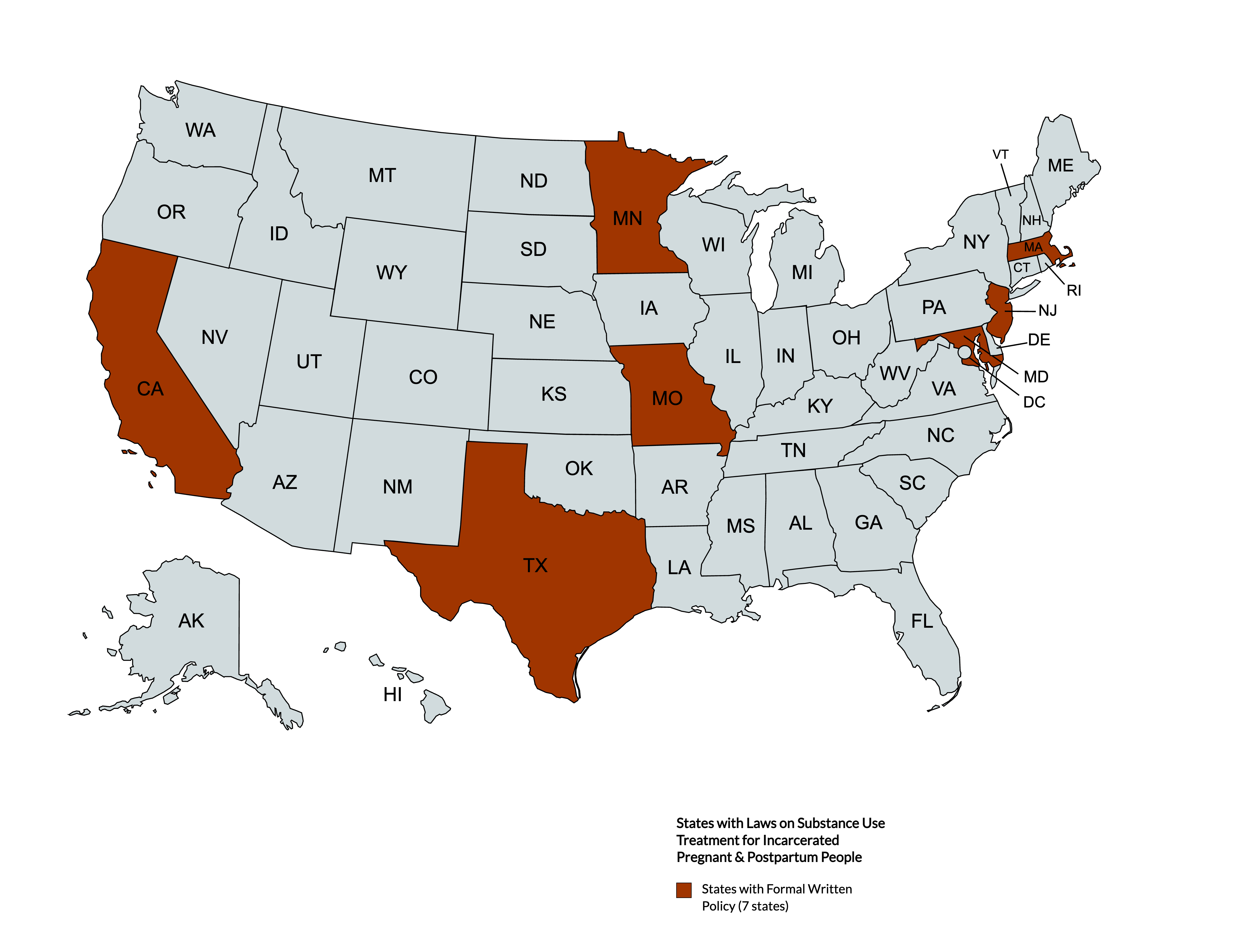

Executive Summary: In the U.S., over 60% of incarcerated pregnant people are in custody for non-violent drug offenses. Only 7 states had statutes related to treatment of substance use disorders in pregnant incarcerated populations despite the evidence that many incarcerated pregnant people struggle with substance use.

Background:

The National Household Survey on Drug Use conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that between 2003 and 2018, there was a 0.6% increase in binge alcohol use during pregnancy. In 2018, the prevalence of tobacco use/smoking in pregnant people was 11.6%, and the prevalence of alcohol use among pregnant people was 9.9%.1 Rates of opioid use disorder (OUD) in pregnancy have increased substantially in the last decade.2,3 Between 2010 and 2017, the number of women with opioid-related diagnoses documented at birth increased by 131%.² During that same time period, the prevalence of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome increased by 82% nationally.2,3

Over the past several decades, there has been a substantial increase in the number of people in U.S. prisons and jails.4 Between 1980 and 2022, there was more than a 650% increase in the population of incarcerated women.5,6 Among this growing incarcerated population, pregnant people are especially vulnerable, with about ~3000 and ~55000 pregnant people entering prisons and jails each year, respectively.7,8 Many incarcerated pregnant people enter into the system with a substance use disorder (SUD). This reflects an urgent need for substance use treatment tailored to the needs of pregnant and postpartum incarcerated people.9

Pregnant and postpartum incarcerated individuals with SUD face a unique set of risks to their well-being including: the impact of substance use on their mental health and the health of the fetus; the impact of abrupt substance use cessation and withdrawal on the incarcerated person’s well-being; the potential for return to use during the postpartum period, during which time many are susceptible to postpartum depression, at increased risk for involvement in child protective services, and are at increased risk of death. This policy brief seeks to detail findings from a review by Steely Smith et. al (2023), “State Laws on Substance Use Treatment for Incarcerated Pregnant and Postpartum People,” which examines existing laws provisioning treatment or specialized healthcare for pregnant and postpartum incarcerated people struggling with SUD in the U.S.9

Summary of State Laws:

Forty-three states had at least one law specific to pregnant or postpartum incarcerated people; of these states, only seven had laws related to screening for SUD and/or treatment of SUD in pregnant incarcerated people. None of these states had laws for treating SUD in postpartum incarcerated people. Overall, Texas, California, Minnesota, Maryland, New Jersey, Missouri, and Massachusetts jointly contributed a total of 14 statutes pertaining to substance use among pregnant and postpartum incarcerated populations in the U.S.

California: The state has eight statutes relevant to substance use screening and treatment for pregnant or lactating incarcerated people, educating incarcerated pregnant people about withdrawal, diversion programs as an alternative to sentencing for mothers facing prison or jail time (including eligibility requirements), and the appropriation of funds for new residential facilities for pregnant people.

Massachusetts: Massachusetts has one law relevant to substance use in pregnant incarcerated people; this statute requires pregnancy counseling before subsequent release of pregnant and postpartum incarcerated people who have an SUD.

Missouri: Missouri has three laws relevant to substance use among pregnant incarcerated people. These statutes pertain to the creation of a pilot diversion program, its eligibility requirements, and the allocation of funds for its maintenance.

Minnesota: Minnesota has one law addressing SUD in its pregnant incarcerated population. The statute focuses on educating correctional staff about how to meet the needs of incarcerated women whose fetuses are at risk for fetal alcohol syndrome.

Maryland: Maryland has one law related to pregnant incarcerated people who have an SUD. This statute directs correctional facilities to have policies on the medical care of pregnant incarcerated people with SUD.

New Jersey: New Jersey’s law requires wardens to allow pregnant incarcerated people access to residential drug use and mental health diversion programs if they meet certain eligibility requirements.

Texas: Texas has six statutes relevant to screening, education, or treatment for SUD in incarcerated pregnant and postpartum populations. Two statutes related to screening focus on creating programs to identify pregnant incarcerated people struggling with alcohol use or alcohol use disorder; three statutes related to education focus on informing incarcerated pregnant people about the risks of alcohol and drug consumption during pregnancy; one statute on treatment relates to an intervention on alcohol use among incarcerated pregnant people who screened positive for alcohol use disorder/alcohol use during pregnancy.

A comprehensive, sortable table of these summaries (including links to relevant statutes) can be accessed here.

Recommendations:

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP) recommend “early, universal screening for substance use as part of comprehensive prenatal” and postpartum care.10,11 Congress and state legislatures could create new policies mandating all prisons and jails to provide both SUD screening and treatment for all pregnant and postpartum people involved in the criminal legal system. These statutes should refrain from using stigmatizing language when referring to incarcerated individuals.

- Prisons and jails should provide evidence-based treatment for SUD. Treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) should include access to medication assisted treatment–including methadone and buprenorphine–for pregnant and postpartum people in custody and upon re-entry.

- All prisons, jails, and detention facilities should be vigilant in creating programs to screen and treat SUD among all pregnant and postpartum people in custody. This screening and treatment should be humane, trauma-informed, and honor personal dignity, recognizing the role that trauma often plays in the development of SUD.

- States should continue to implement alternatives to incarceration, especially for pregnant and postpartum incarcerated individuals overcoming a SUD. Since many incarcerated individuals struggle with SUD and are tried for non-violent drug offenses, it is apt to consider diversion programs as the first line of sentencing, especially for pregnant and postpartum people. Congress could restructure funding allocation to make more funding available to these diversion programs. Substance use treatment should be a part of an easily accessible, free social service.

- As of September 2023, the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) has allocated $9,000,000 towards the Screening and Treatment for Maternal Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders to 12 states including California, Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia.12 States receiving funding for the screening and treatment of SUD in pregnant people should prioritize implementing this in prisons and jails, where it is estimated that over 70% of women struggle with a SUD. Programs targeted at treating SUD in incarcerated pregnant and postpartum people should consider offering sustained mental health counseling services to get at the root cause of the SUD; this could reduce risk for relapse, especially for incarcerated persons in the postpartum period at risk for postpartum depression and overdose.

- Legislation could be introduced that identifies SUD as a serious medical need so that prisons and jails have a constitutional obligation to provide an adequate standard of care for SUD, especially among pregnant and postpartum incarcerated individuals.

Conclusion:

Only seven states have laws related to substance use in incarcerated pregnant and postpartum people. Most states are neglecting this already vulnerable maternal and child health group. As it stands, pregnant and postpartum incarcerated people with SUD are in critical need of healthcare that is tailored to address their unique needs.

Suggested Citation:

Augustin, D., Steely Smith, M. K., Zielinski, M. J., Sufrin, C., Kramer, C. T., Benning, S. J., Laine, R., & Shlafer, R. J., (2023). State Laws on Substance Use Treatment for Incarcerated Pregnant and Postpartum People. Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health, University of Minnesota.

This brief is based on the article: Steely Smith, M. K., Zielinski, M. J., Sufrin, C., Kramer, C. T., Benning, S. J., Laine, R., & Shlafer, R. J. (2023). State Laws on Substance Use Treatment for Incarcerated Pregnant and Postpartum People. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 11782218231195556. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218231195556

This brief is a joint publication by authors from the: Department of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas (AR) for Medical Sciences; Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of AR at Fayetteville; Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota (UMN); Department of Pediatrics, UMN

Designed by Cassie Mohawk, The Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health (mch@umn.edu).

Acknowledgements:

Funding for this effort was provided by the Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health at the University of Minnesota. The Center is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number T76MC00005-67-00 for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health in the amount of $1,750,000. This information or content and conclusions of related outreach products are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. The original manuscript preparation was also supported by T32DA022981 (PI: Kilts), K23DA048162 (PI: Zielinski) and R34DA056014 (PI: Sufrin) which provided salary support for the first, second and third authors.

References:

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/national-survey-drug-use-and-healthnsduh-2018-nid18757

- Hirai, A. H., Ko, J. Y., Owens, P. L., Stocks, C., & Patrick, S. W. (2021). Neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid-related diagnoses in the US, 2010-2017. JAMA, 325(2), 146-155.

- Haight, S. C., Ko, J. Y., Tong, V. T., Bohn, M. K., & Callaghan, M. D. (2018). Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization – United States 1999-2014, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(31), 845-849. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://dx.doi.org /10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a1

- Kajstura, A., & Sawyer, W. Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html

- Zeng, Z. (2023). Jail Inmates in 2022 – Statistical Tables. Access December 17, 2023. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/jail-inmates-2022-statistical-tables

- Carson, E.A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2022-statistical-tables

- Sufrin C, Beal L, Clarke J, Jones R, & Mosher WD. Pregnancy outcomes in US prisons, 2016–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:799-805.

- Sufrin C, Jones RK, Mosher WD, Beal L. Pregnancy prevalence and outcomes in U.S. Jails. Jails Obs Gynecol. 2020;135:1177-1183.

- Steely Smith MK, Zielinski MJ, Sufrin C, Kramer CT, Benning SJ, Laine R, & Shlafer RJ. State Laws on Substance Use Treatment for Incarcerated Pregnant and Postpartum People. Sage Pub. 2023.

- Association for Maternal and Child Health Programs. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for Pregnant and Postpartum Women. 2020. Accessed November 16, 2023.

- ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Reproductive health care for incarcerated women and adolescent females. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120:425–429.

- Health Resources & Services Administration (2023). Screening and Treatment for Maternal Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Accessed December 16, 2023. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/screening-treatment-maternal-mental-health-substance-use-disorders-mmhsud

Questions

Contact jiwc @ umn.edu