#UMNMCH student Dr. Laurel Cederberg (MPH 2024) wrote this reflection detailing her involvement with the Vision Health Task Force. The task force is dedicated to addressing vision health equity, particularly through their “Little Eyes, Big Eyes” project for Native American children and families in Minnesota. Drawing from her hands-on experience, Laurel conducted an extensive literature review on vision health among Native American children and adults, spanning the years 1976 to 2022. This research endeavor has subsequently inspired her to embark on her own project, focusing on pediatric vision screening as well as the vision health of children and teens who self-identify as Native American within the HealthPartners care system in Minnesota.

Path to UMN SPH Program

I have practiced general pediatric and adolescent medicine for over 25 years at the HealthPartners Como Clinic in St. Paul, MN. Over the past years, like many healthcare providers, I have been frustrated trying to improve the health of one patient or one family at a time in the clinic setting when patients and their parents had difficulties making individual changes that I recommend — increased physical activity or healthier diets, for example, or making appointments for further evaluations that may not be covered by their insurance.

For the past 12 years, I also have collaborated with Dr. Henry Balfour, Jr. at the University of Minnesota (UMN) Viral Research Laboratory (the “Mono Project”) researching Epstein Barr virus (EBV), which can cause infectious mononucleosis or “mono.” EBV is also an “oncogenic” or cancer-causing virus. In fact, EBV was the first virus discovered to be associated with a type of cancer – Burkitt’s lymphoma in 1964.1 Dr. Balfour and his lab staff were developing a vaccine and wanted to figure out at what age to administer this vaccine. My patients at the HealthPartners Como clinic helped with two studies that looked at when, or at what age, kids get EBV, 2,3 and parents participated in one study that explored how adults may be the main source of the EBV for their young children.4 Our collaborative studies found that Black children get EBV much earlier than white children,2 and that Black parents, along with other parents of color, shed EBV in their saliva at higher rates compared to white parents, which we hypothesized was a cause for the spread of EBV at higher rates to their younger children compared to white parents.4 We identified more disparities, but we could not clearly answer “why?” I contacted experts in diversity and equity at the UMN School of Public Health to see if there was interest in collaboration. However, they kindly declined due to time constraints.

So to better understand the effects of negative social determinants of health that my pediatric patients and their families were facing, explore the underlying causes of the persistent health disparities by race/ethnicity seen in our clinical EBV studies, and how to get away from the age-old patterns of using race/ethnicity as a proxy for racism5, I applied to the Maternal Child Health (MCH) MPH program at the UMN. I was supported by my pediatric colleague, Elsa Keeler, MD, MPH ‘16, and lead researcher on the Mono Project, Jenn Geris, MPH ’18, PhD ’22, who taught me so much about epidemiology and encouraged me to pursue the graduate minor in epidemiology.

Laurel’s Deployment with Minneapolis Public Schools/Minnesota Vision Health Task Force

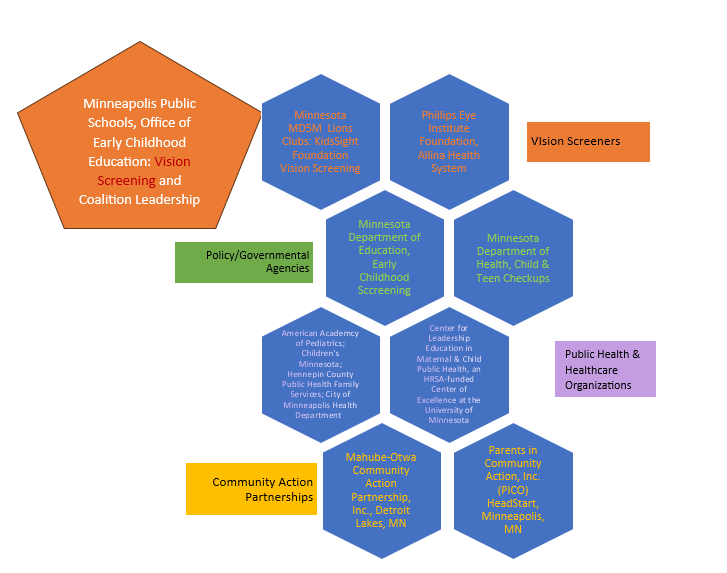

As an intern supported by the Center for Leadership in Maternal & Child Public Health at the University of Minnesota, I have experienced the energy of a committed and thriving community coalition, the Minnesota Vision Health Task Force. Led by the director of the Minneapolis Public Schools’ Office of Early Childhood Education, Cynthia Hillyer, RN, LSN, MPA, the coalition is made up of a variety of stakeholders who aim to improve vision screening and vision health in all children in Minnesota. They have worked in the past with the national Prevent Blindness team and have leveraged the new technology in “instrument-based” vision screening (hand-held photoscreening devices) in Early Childhood Screening (ages 3-5 years) and school screening K-7. During that 2017-2018 school year when they started using the photoscreening device, 169 students were diagnosed with a vision condition that needed treatment with glasses, compared to only 35 who needed glasses the year prior.6 Compared to using the traditional wall chart, the screeners achieved a 265% increase in vision referrals with photoscreening, and a final 483% increased rate of treatment with glasses for vision problems diagnosed by an eye specialist.6

Minnesota’s Initiative to Improve Vision Health in Native American Communities

Currently, the Task Force is focused on the vision health of Native Americans — young and old — with its “Little Eyes, Big Eyes” initiative that “will support Native Community capacity, local healthcare clinics and community organizations in vision screening and follow up care by

- building and sustaining an eye health system of care that will have short- and long-term benefits, positively impacting eye health across the lifespan.

- providing instrument screeners, technical assistance and training (including support in developing care coordination processes and reducing systems barriers to accessing eye care services)

- addressing the vision health of whole families, prioritizing the needs for children and elders and will align strategies of the MD5M Lions Clubs, the Minnesota PMAP health insurers, Federal Head Start Programs and the Minnesota Department of Education Early Childhood Screening Program.”7

National Collaboration to Improve Vision Health in Native Americans

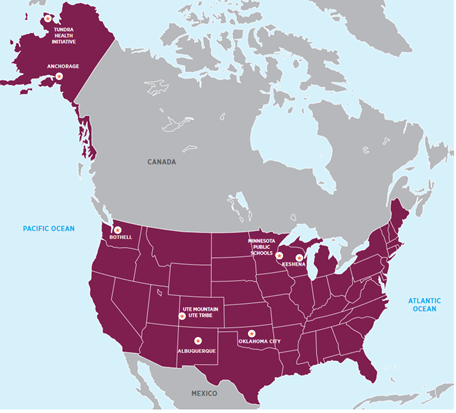

The Task Force coalition is one of 8 local partners in the US to receive grant funding from the global Seva Foundation as part of its American Indian Sight Initiative (AISI).

This initiative’s goal is “to improve eye health through collaborative, locally based partnerships, [with a] focus on the most common and treatable eye health issues found in American Indian communities: the need for eye health screening, medical treatment, and eyeglasses.”8 I was able to participate in regular AISI “Listening Circles” meetings and hear updates amongst the grantees and the grantor Seva Foundation, and see great cross-pollination of ideas and solutions to vision health care delivery. I was impressed how our Minnesota “Little Eyes, Big Eyes” team often was able to support and offer suggestions to the other vision health grantees in Alaska, Colorado, Washington, and Wisconsin.8

The MN Vision Health Task Force Work

Each month with the Minnesota Vision Health Task Force, I was able to experience how committed government, policy, health, education, and community members came together to work with Native American stakeholders to improve vision in kids. I saw the energy and dedication of

- the Native and non-Native leaders of the Mahube-Otwa Community Action Partnership, Inc. in the Detroit Lakes, MN area who serve communities that include Native Americans,

- community volunteers with the local Lions Clubs who did the vision screening at an educational school powwow in Detroit Lakes, MN and the local MD5M Lions Club with its Kidsight Foundation that offers year-round vision screening in the Twin Cities area in preschools, schools, and at public events,

- the Minneapolis (MPS) Early Childhood school nurse who used the Prevent Blindness education resources, got the certification to screen adults at community events, and procured vouchers for adults who were screened at a school powwow event in Detroit Lakes, MN for cost-free corrective lenses.

- the MPS Early Childhood Screening staff who helped with screening at the Baby’s Space preschool at the Little Earth Community in the Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis,

- the MPS Native Education staff and fellow University of Minnesota School of Public Health student and intern, Cassie Mohawk, who designed the “Little Eyes, Big Eyes” initiative awareness campaign materials,

- the community-based Phillips Eye Institute (historic) community vision screening program which routinely screens all children in both the Minneapolis Public School District and St. Paul Public School District, in addition to its Kirby Puckett Eye Mobile Program (affiliated with the Allina Health Systems),

- other health care systems (Hennepin County Medical Center, Children’s of Minnesota, Hospital and Clinics), and

- the governmental policy members at the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and the Minnesota Department of Education (MDE).

Vision Screening in Minnesota

I have learned how vision screening in Minnesota has been done in many settings: at well-child visits in clinics; at school-readiness evaluations before entrance into kindergarten (MDE) by the school district teams and HeadStart Programs; and during the school years through school-based vision screening programs. I was surprised by how vision screening has been provided through these multiple agencies and providers. However, with this overlap of services, is there a risk of vision problems being missed?

Through my internship, I learned that the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) “administers” the Child and Teen Check ups (C&TC) in Minnesota, and the Minnesota Department of Health “provides health consultation and technical assistance to the Department of Human Services and programs that provide C&TC screening exam components9 in accordance with the C&TC Schedule of Age-Related Screening Standards.” These standards include “clinical recommendations about best practices in well-child visits and training on required screening components for C&TC providers, C&TC Coordinators, local public health, Head Start programs, and others who provide screening for children.”10

Vision screening is required at all medical well-child visits for children and youth/young adults 3 to 21 years of age9 insured by Medicaid at their Child and Teen Checkups (C&TC). C&TC is Minnesota’s version of the federal Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program. But vision screening and reporting of results surprisingly is not required at medical well-child visits covered by private insurance, although it is recommended by a myriad of national professional organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health.

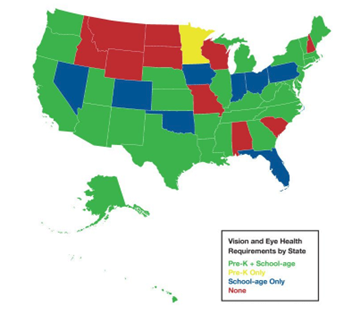

Requirements for vision screening vary widely by state. It appears that Minnesota is the only state that follows the narrower US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) statement on Vision in Children Ages 6 Months to 5 Years: Screening, while ten states (seen as red in the map figure below from a 2021 study by Wahl, et al.) do not have any vision screening requirements.11 Minnesota is the only state in the US (seen as yellow in the map below) that requires vision screening only in the early childhood years (age 3 to 5) and not later during the school-aged years, like those states that are noted in green or blue in the map below do.11

Per the Minnesota Statutes 2022, section 121A.17 with updates in 2023 via CHAPTER 54–H.F.No. 2292 Subd. 3. Screening program:

“Early childhood developmental screening helps a school district identify children who may benefit from district and community resources available to help in their development. Early childhood developmental screening includes a vision screening that helps detect potential eye problems but is not a substitute for a comprehensive eye exam. … For the purposes of this section, ‘comprehensive vision examination’ means a vision examination performed by an optometrist or ophthalmologist.”12

Thus, vision screenings performed by a program in a child’s Head Start daycare, at Early Childhood Screening, at the school, or at the healthcare provider’s office during the well-child visit all will lead to the necessary referral to the eye specialists: the optometrist or ophthalmologist.

Intern Experiences and Contributions

During the summer of 2022, I took Professor Genelle Lamont’s Public Health Summer Institute 7200-108 *87282 course on “American Indian Health and Wellness, Understanding and Applying the ‘Other Public Health System,” which focused on Native American health and tribal public health systems. It was a week of intense learning with many inspiring guest speakers from local tribal clinics and the leader of the Great Lakes Area Tribal Health Board. Professor Lamont’s powerful course helped me to continue to process and better understand the historical trauma long suffered by Native Americans as well as to be more culturally aware of and understand the current health care needs in Native communities. With the ongoing “Little Eyes, Big Eyes” initiative, I see the benefits of collaboration with Native stakeholders and their input on how best to improve vision health in Native communities.

With new epidemiology and public health research skills, I performed an extensive PUBMED literature search about vision health in Native American children and adults from 1976 to 2022. Only 48 pertinent articles were found that focused on the prevalence of vision-loss-related disease in Native Americans of all ages and/or their historical lack of sufficient access to vision care.

During this forty-six-year-long literature search span, there were only 27 articles about Native American children’s and youths’ vision health (22) and pediatric vision health care (5). Most (24) of the articles are out-of-date, published over 10 years ago. Two of the “recent” pediatric articles about rates of vision-loss-related conditions in Native American children were published in 2014,13, 14 while the only recent study about pediatric strabismus from 2021 merely mentions that 2 children or 2.5% of their sample self-identified as Native American.15

For Task Force members and community stakeholders, I developed vision health educational materials to highlight the importance of screening for vision-loss-related conditions in young children and treating them before the age of 7 years to preserve vision, as well as the history of photoscreening technology and the various guidelines for its use. I explored a newer photoscreening product that is used in my clinic as a possible screening tool update, but the team determined that the darkened room needed with the device would not work well in community or school settings. I presented specific information about Minnesota’s 11 federally-recognized Native American tribes and their health care systems, the Indian Health Service in Minnesota, the Great Lakes Area Tribal Health Board (GLATHB)16 and the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Epidemiology Center (GLITEC)17 which is one of 12 national Tribal Epidemiology Centers. Along with Task Force leaders, I introduced the “Little Eyes, Big Eyes” initiative at the February 2023 meeting with GLATHB and GLITEC.

My work with the Minnesota Vision Health Task Force coalition led to the development of my own research project on pediatric vision screening in general and the specific vision health of those children and teens who self-identify as Native American within the HealthPartners care system in Minnesota. The study design, data collection, and analysis counted towards my MCH MPH Integrated Learning Experience (ILE) and was supported by the Pregnancy and Child Health Research Center at the HealthPartners Institute in Bloomington, MN.

Since my deployment ended, I have continued to participate as a community member with the Task Force as I work to improve vision health screening at my workplace and across the state. I will highlight our work at the upcoming AMCHP “Partnering for Purpose” meeting in Oakland, CA in April 2024.

References

- Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus Particles in Cultured Lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s Lymphoma. Lancet. Mar 28 1964;1(7335):702-3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(64)91524-7

- Condon LM, Cederberg LE, Rabinovitch MD, et al. Age-specific prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus infection among Minnesota children: effects of race/ethnicity and family environment. Clin Infect Dis. Aug 15 2014;59(4):501-8. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu342

- Cederberg, LE, Geris, JM, Chang, M., et al…. Henry H. Balfour, Jr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) Infection in Preadolescent Children: A Prospective Study. (Publication pending). This study was presented in part at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in Denver, CO on April 24, 2022.

- Cederberg LE, Rabinovitch MD, Grimm-Geris JM, et al. Epstein-Barr Virus DNA in Parental Oral Secretions: A Potential Source of Infection for Their Young Children. Clin Infect Dis. Jan 7 2019;68(2):306-312. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy464

- Cederberg LE. It’s not just Black and White anymore: Incorporating health equity and social justice lenses in clinical research and health care to explain and address health disparities. Opinion Editorial. Public Health Review. June 2022 2022;5(2)

- n.d. MN Vision Health Task Force. University of Minnesota School of Public Health. 2023. https://mch.umn.edu/resources/mnvhtf/

- n.d. Voices From the Field: Interview with Cindy Hillyer: Promoting Equity in Children’s Vision Health. September 20, 2023, 2020. https://sites.ed.gov/osers/2020/08/voices-from-the-field-interview-with-cindy-hillyer/?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term

- n.d. Seva.org: United States Fact Sheet Seva Foundation Accessed September 20, 2023, 2023. https://www.seva.org/pdf/Seva_Country_Fact_Sheets_US.pdf

- n.d. Minnesota Child and Teen Checkups (C&TC) Schedule of Age-Related Screening Standards. 2023. https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-3379-ENG

- n.d. Child and Teen Check ups. Accessed August 20, 2023, 2023. https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/childrenyouth/ctc/index.html

- Wahl MD, Fishman D, Block SS, et al. A Comprehensive Review of State Vision Screening Mandates for Schoolchildren in the United States. Optom Vis Sci. May 1 2021;98(5):490-499. doi:10.1097/opx.0000000000001686

- n.d. Minnesota Statutes 2022: Screening Programs Minnesota Session Laws – 2023, Regular Session. Accessed September 20, 2023, 2023. https://www.revisor.mn.gov/laws/2023/0/Session+Law/Chapter/54/

- n.d. Instrument Based Vision Screening. Accessed August 20, 2023, 2023. https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/childrenyouth/ctc/visionscreen/screening.html

- Huang J, Maguire MG, Ciner E, et al. Risk factors for astigmatism in the Vision in Preschoolers Study. Optom Vis Sci. May 2014;91(5):514-21. doi:10.1097/opx.0000000000000242

- Ying GS, Maguire MG, Cyert LA, et al. Prevalence of vision disorders by racial and ethnic group among children participating in head start. Ophthalmology. Mar 2014;121(3):630-6. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.036

- L. A. Jones-Jordan, L. T. Sinnott, R. H. Chu, S. A. Cotter, R. N. Kleinstein, R. E. Manny, et al. Myopia Progression as a Function of Sex, Age, and Ethnicity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2021 Vol. 62 Issue 10 Pages 36n.d. Great Lakes Area Tribal Health Board: What we do. Great Lakes Area Tribal Health Board. 2022. https://glathb.org/what-we-do/

- n.d. Great Lakes Tribal Epidemiology Center: Overview Accessed September 2022, 2022. https://www.glitc.org/programs/epidemiology-and-education/great-lakes-inter-tribal-epidemiology-center/overview-glitec/

BIO

Laurel Cederberg, MD, (she/her/hers) will finish her MCH MPH degree in Spring 2024. Excellence and equity in pediatric health care have been her passions over the years as she has worked with children and families in Minneapolis, MN during medical school, Oakland, CA during her pediatric residency training, and then in Stockholm, Sweden and St. Paul, MN as a board-certified pediatrician. After graduating from the UMN School of Public Health, Laurel hopes to continue to strive for excellence in pediatric care at the HealthPartners Como Clinic Department of Pediatrics, while also pursuing clinical research that promotes equity for children and teens and advocacy for improvement in children’s and teens’ health at the policy level.

–Read Student Spotlight archives

Interested in learning more about getting a degree in MCH? Visit our MCH Program page for more information.

#UMNMCH #UMNproud #UMNdriven