A State Policy Brief from the National University-Based Collaborative on Justice-Involved Women & Children (JIWC)

March 2024

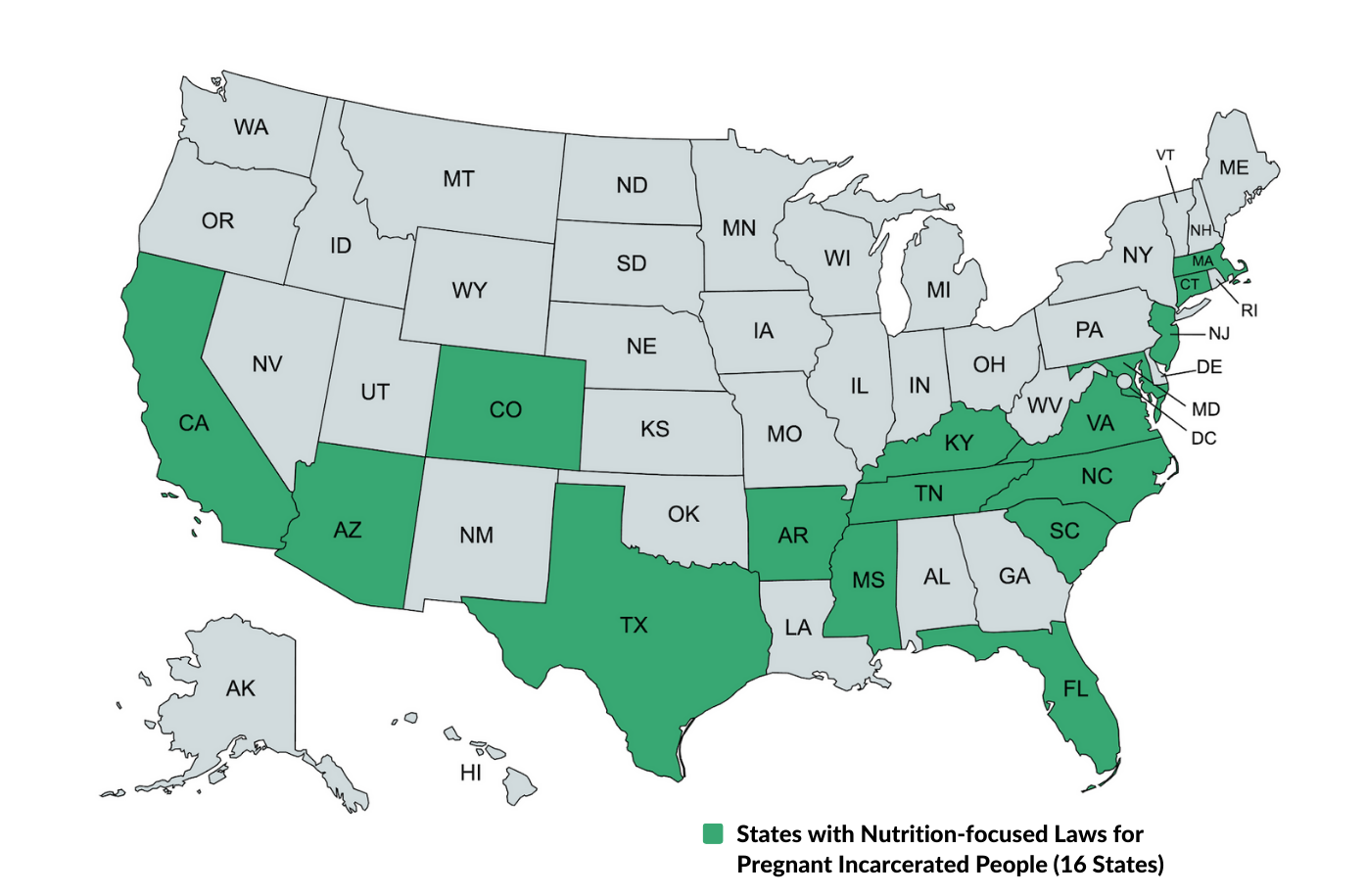

Executive Summary: No federal statutes cover prenatal nutrition for incarcerated pregnant people and fewer than one-third of U.S. states have passed laws requiring health-promoting nutrition policies for pregnant people who are incarcerated. Of the 16 states that have passed legislation, none cover all of the national recommendations to ensure proper nutrition for this population.

Background:

Adequate nutrition is important for having a healthy pregnancy. Given this, national guidelines and recommendations outline the need for fruits and vegetables, hydration, and prenatal supplements, while staying away from foods and substances that can cause harm during pregnancy.1,2,3,4,5 Diets that do not provide proper nutrition during pregnancy can increase risks for poor outcomes for the pregnant person and fetus. For example, anemia during pregnancy is associated with increased risk for preeclampsia, postpartum depression, and postpartum hemorrhage, which can lead to maternal complications and death.6,7 Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy can also contribute to infant birth weight that is too high or too low, and to the development of birth defects.8

Access to adequate nutrition is particularly important for individuals who are pregnant while incarcerated. Pregnant people who are incarcerated are more likely to be impacted by structural racism and have less access to the resources they need for a healthy pregnancy, including access to prenatal care, before they are incarcerated.9 These factors, in addition to harms associated with incarceration (e.g., social isolation), have been associated with pregnancy complications.9 Therefore, enhanced prenatal support is needed for pregnant incarcerated people.9

Although limited, existing research suggests that incarcerated people may not be getting the nutrition they need. Studies evaluating the nutritional content of menus and commissary items found that food provided in prisons and jails are high in calories and fat, while low in key vitamins and minerals.10,11,12,13,14 When comparing these meals to the recommended servings for pregnant people specifically, the amount of magnesium and fiber were found to be too low.15 Additionally, the increase in high temperatures in prisons and jails make access to water and other forms of hydration important, but people in prisons and jails might not have access to water when they need it.16

Summary of State Laws:

Sixteen states (AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, FL, KY, MA, MD, MS, NC, NJ, SC, TN, TX, and VA) have passed legislation requiring health promoting nutritional policies for pregnant people who are incarcerated.

Prenatal Diet (15 States): Fifteen states (AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, KY, MA, MD, MS, NC, NJ, SC, TN, TX, and VA) have statutes related to providing an adequate diet to pregnant people who are incarcerated.

Prenatal Vitamins (11 States): Eleven states (AZ, AR, CA, CT, MA, MS, NC, NJ, SC, TX, and VA) have statutes regarding access to prenatal vitamins/dietary supplements.

Supplemental Food (2 States): Two states (FL and TN) are the only two states with statutes pertaining to access to supplemental food during pregnancy.

Additional Hydration (0 States): No states have statutes related to additional hydration or expanded access to water during pregnancy.

Prenatal Nutrition Education (4 States): Four states (MA, MD, CO, and CT) have statutes related to nutrition counseling or access to written information on prenatal nutrition.

A complete list of the state statutes can be found here.

A Closer Look:

Providing a Prenatal Diet Following Federal Guidelines: While statutes exist, they do not include detailed information about the type of food, frequency of meals, or any other description of the recommended diet for this population. Thus, it is unknown whether these diets meet all the guidelines for pregnant people outlined by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the Institute of Medicine.1,2,3,4,5 Kentucky and Maryland laws say only that pregnant people who are incarcerated be given “adequate nutrition” and have their “nutritional needs” met. Colorado requires only that pregnant people who are incarcerated be provided with “healthy foods.” Only five states require that a medically approved diet meet prenatal standards; nine states require that diets provided to pregnant people who are incarcerated be approved by a medical professional.

Access to Prenatal Vitamins: Of the 11 states with statutes, seven assert that the prenatal vitamins be recommended by a healthcare provider, although the type of healthcare provider is not the same across states. California is the only state with statutes specifying that supplements be given daily. No state statutes include information about the supplements’ contents, ingredients, or amount. Further, no state requires prisons and jails report compliance with prenatal vitamin access to an outside organization.

Supplemental Food Appropriate for the Trimester of Pregnancy: Florida and Tennessee statutes contain vague language (e.g., “supplemental provisions between meals”) with no details about the nutritional content or additional daily calories provided, if appropriate.

Prenatal Nutrition Education: The language used in Massachusetts, Maryland, Colorado, and Connecticut statutes is brief. There are no descriptions about the type or content of this education or counseling. Massachusetts states that pregnant people who are incarcerated be given “written information regarding prenatal nutrition.” Maryland’s law only requires that pregnant individuals be provided with “nutritional needs and counseling.” Of note, Connecticut requires that information be provided in a form that is “reasonably understood.”

Statutes for Prisons vs. Jails:

State statutes do not always clearly outline whether the statute applies to prisons, jails, or to both. However, more often than not, statutes apply to pregnant people in prisons and not jails or other short-term detention centers. This is a concern, as pregnant people are admitted to jails more often than prisons.9

Enforcement:

While state laws providing access to adequate nutrition for this population is an important step, it is not enough to ensure that prisons and jails will implement these policies. There is evidence from several states that, even though laws have been passed regarding the care and treatment of pregnant people (e.g., prohibiting the use of restraints), implementation of these laws is not consistent.17,18

Our policy scan found no mechanisms for enforcement of existing nutritional statutes at the state level. The lack of mechanisms to enforce and provide oversight means that access to adequate nutrition and hydration for pregnant people who are incarcerated – even in the few states in which prenatal nutrition-related statutes have been passed – might not be protected.

Recommendations:

States have the opportunity to address the adequate nutrition of incarcerated pregnant people by passing or amending legislation that aligns with current nutritional guidelines for pregnant people. We recommend the following:

- Test for pregnancy on admission and provide comprehensive and adequate nutrition for pregnant people, including prenatal vitamins, diets aligned with national standards, adequate hydration, and supplemental food as appropriate, as well as providing prenatal nutrition education and counseling.

- Include mechanisms to assess and enforce compliance with the law.

- Encourage professional health organizations such as the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Commission on Correctional Health Care, and the American Public Health Association to release position statements calling for adequate nutrition and hydration for incarcerated pregnant people.

Suggested Citation:

Suggested citation: Shalev, T., Vitagliano, J., Mason, E., Shlafer, R., Saunders, J., Stang, J.S., & Kotlar, B. (2024). State Laws on Adequate Nutrition for People Who Are Pregnant While Incarcerated. Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health, University of Minnesota.

This brief is based on the March 2024 Journal of Correctional Health Care article Forgotten fundamentals: a review of legislation on nutrition for incarcerated pregnant people by Vitagliano, J.; Shalev, T.; Saunders, J.; Mason, E.; Stang, J.; Shlafer, R.; and Kotlar, B.

Designed by Cassie Mohawk, The Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health (mch@umn.edu).

Acknowledgements:

The Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health | The authors of this publication are housed at Centers supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under the following grant names/numbers: the UMN Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health (grant #T76MC00005), Harvard Maternal and Child Health Training Grant (grant #T76MC00001), UIC-SPH Center of Excellence in Maternal and Child Health (grant #T76MC00009), and the UMN Leadership Education Training Program in MCH Nutrition (grant#T76 MC00009). This information or content and conclusions of our outreach products are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Institute of Medicine. (1997). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/5776

- Institute of Medicine. (1998). Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/6015

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10026

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- Rasmussen, K. M., Yaktine, A. L., & Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines. (2009). Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. National Academies Press.

- Faysal, H., Araji, T., & Ahmadzia, H. K. (2023). Recognizing who is at risk for postpartum hemorrhage: targeting anemic women and scoring systems for clinical use. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 5(2), 100745–100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100745

- Lao, T. T., Wong, L. L., Hui, S. Y. A., & Sahota, D. S. (2022). Iron Deficiency Anaemia and Atonic Postpartum Haemorrhage Following Labour. Reproductive Sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 29(4), 1102–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-021-00534-1

- Procter, Sandra B., PhD, RD/LD, & Campbell, Christina G., PhD, RD. (2014). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition and Lifestyle for a Healthy Pregnancy Outcome. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(7), 1099–1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.05.005

- Sufrin, C., Beal, L., Clarke, J., Jones, R., & Mosher, W. D. (2019). Pregnancy Outcomes in US Prisons, 2016–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109(5), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006

- Holliday, M. K., & Richardson, K. M. (2021). Nutrition in Midwestern State Department of Corrections Prisons: A Comparison of Nutritional Offerings With Commonly Utilized Nutritional Standards. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 27(3), 154–160. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jchc.19.08.0067

- Cook, E. A., Lee, Y. M., White, B. D., & Gropper, S. S. (2015). The Diet of Inmates. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 21(4), 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345815600160

- Collins, S. A., & Thompson, S. H. (2012). What Are We Feeding Our Inmates? Journal of Correctional Health Care, 18(3), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345812444875

- Mommaerts, K., Lopez, N. V., Camplain, C., Keene, C., Hale, A. M., & Camplain, R. (2022). Nutrition availability for those incarcerated in jail: Implications for mental health. International Journal of Prisoner Health. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-02-2022-0009

- Lopez, N. V., Spilkin, A., Brauer, J., Phillips, R., Kuss, B., Delio, G., & Camplain, R. (2022). Nutritional adequacy of meals and commissary items provided to individuals incarcerated in a southwest, rural county jail in the United States. BMC Nutrition, 8(1), 96–96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-022-00593-w

- Shlafer, R. J., Stang, J., Dallaire, D., Forestell, C. A., & Hellerstedt, W. (2017). Best Practices for Nutrition Care of Pregnant Women in Prison. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 23(3), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345817716567

- Skarha, J., Peterson, M., Rich, J. D., & Dosa, D. (2020). An Overlooked Crisis: Extreme Temperature Exposures in Incarceration Settings. American Journal of Public Health, 110(S1), S41–S42. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305453

- Kuhlik, L. (2017). Pregnancy behind bars: The constitutional argument for reproductive healthcare access in prison. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 52(2), 501–535.

- Tapia, N. D., & Vaughn, M. S. (2010). Legal Issues Regarding Medical Care for Pregnant Inmates. The Prison Journal (Philadelphia, Pa.), 90(4), 417–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885510382211