A State Policy Brief from the National University-Based Collaborative on Justice-Involved Women & Children (JIWC)

May 2023

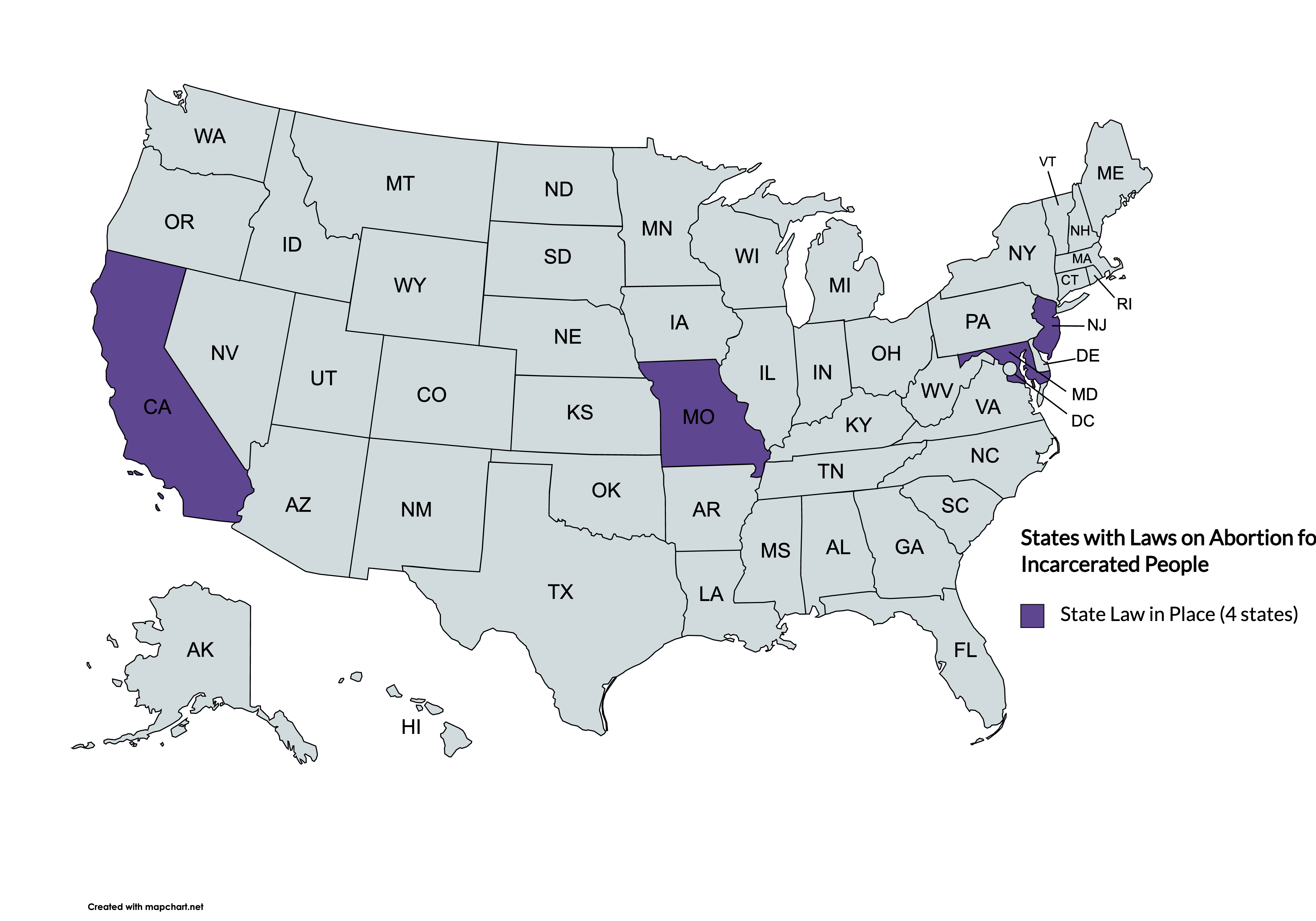

Executive Summary: Without the constitutional protection of abortion, access is entirely dependent on state laws. Before Roe was overturned, only 4 U.S. states had laws on abortion for incarcerated people in the U.S. In the last year, the legal landscape for abortion has changed dramatically, leaving incarcerated people uniquely vulnerable to the impact of state restrictions and bans.

Background:

In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled to overturn the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson (1). This decision led to an extreme and immediate reduction in the number of abortion clinics providing care across the U.S. Within just six months of the ruling, nearly half of all U.S. states banned or severely restricted abortion care (2). The Dobbs decision will likely have an especially severe impact on incarcerated people (3,4,5).

Before Dobbs: Under Roe, people retained their constitutional right to abortion while incarcerated, though many facilities’ policies made this right difficult to exercise in practice.6 Although Roe never ensured access, its reversal means that incarcerated people in states restricting abortion lost what limited federal protection they once had (4,7).

Post Dobbs: In states where abortion is banned or severely restricted, incarcerated people needing abortions will face formidable (if not insurmountable) barriers to accessing care (5,8,9). Traveling out of state would require significant participation from carceral staff. Additionally, self-managing an abortion would be likely impossible given that incarcerated people do not have free access to mail or supplies. In states where abortion bans make no exception for rape, victims of sexual violence in carceral settings will be forced to carry their pregnancies to term. There are broader implications of incarceration for abortion rights, too: in many states, people with felony convictions are barred from voting and electing officials who might defend reproductive choice in years to come.

State Laws:

Before Roe was overturned the following state laws and federal regulations on abortion for incarcerated people were in place:

In California, pursuant with the Reproductive Privacy Act (2009) which affirms every person’s right to abortion, CA Penal Code § 3405 (2021) states that restrictions or conditions cannot be imposed on incarcerated pregnant persons seeking abortion care. Restrictions might include barriers to transportation, delays in care, or gestational limits inconsistent with state laws.

California also requires that incarcerated people in county jails and state prisons are guaranteed access to pregnancy tests during intake or upon request at any time throughout incarceration under Cal. Penal Code §4023.8 (2020). These tests are voluntary but help to ensure that a person would be aware of their pregnancy status while incarcerated. Incarcerated people who test positive for pregnancy are offered “nondirective, unbiased, and noncoercive” options counseling by a “licensed health care provider or counselor who has been provided with training in reproductive health care.” Carceral staff are not allowed to influence an incarcerated person’s decision and are not able to assess eligibility for abortion services. If an incarcerated person needs an abortion, they should be offered (though not forced to undergo) medical care to terminate the pregnancy.

In Maryland, MD. Correctional Services Code Ann. § 9-601 (2021), requires that incarcerated people have access to information about abortion providers and transportation to care providers who can terminate their pregnancy. Notably, although abortion is legal up until the point of viability in Maryland, the state’s Department of Corrections policy only allows abortion through fourteen weeks. The discrepancies between state law, prison policy, and actual practice have important implications for a person’s access to abortion care.

In 2005, prison officials in Missouri denied an incarcerated person’s request to have an abortion for nearly two months, pushing her point of gestation to around 16-17 weeks. They argued in court that transporting an incarcerated person posed an inordinate security risk for a procedure they deemed to be medically unnecessary. The case went up to the Supreme Court, which in Roe v. Crawford affirmed incarcerated people’s constitutional right to an abortion. Since then, Missouri passed Mo. Ann. Stat. §217.230 which affirmed an incarcerated person’s right to transportation for “elective, non-therapeutic abortions.”

In 1986, two incarcerated women in Monmouth County Correctional Institution (MCCI), New Jersey petitioned for abortions, but their requests were each denied. At that time, the facility’s policy required a pregnant person to apply for court-ordered release and if accepted, to personally arrange for an abortion. People whose petitions were denied were expected to carry their pregnancies to term behind bars. Conversely, MCCI arranged for off-site prenatal appointments for incarcerated pregnant people. In Monmouth County Correctional Inmates v. Lanzaro “Plaintiffs challenge MCCI’s policy of requiring pregnant inmates who desire an abortion to apply for a court-ordered release as an unconstitutional infringement upon their right to privacy, as set forth in Roe v. Wade.” The U.S. Court of Appeals held that abortion constituted a “serious medical need” and that delays or refusals in care infringed on an incarcerated person’s constitutional rights. Since then in New Jersey, NJ Admin Code 10A:16-6.4 (2022) requires that the “Social Services Unit” offers incarcerated pregnant people “religious and social counseling to aid her in making the decision.” If someone decides to terminate the pregnancy, they are required to sign a document acknowledging that they received medical care, was offered counseling, and has chosen to terminate the pregnancy.

Federal Regulations:

U.S. Federal Regulation 28 C.F.R. §551.23 requires that “the Warden shall offer to provide each pregnant inmate with medical, religious, and social counseling to aid her in making the decision whether to carry the pregnancy to full term or to have an elective abortion.” Those who elect to have an abortion must sign a form in recognition of receiving counseling and information on their options. Federal regulations also require that the BOP provide persons with medical and social services related to birth control, pregnancy, child placement, and abortion. Under U.S. Federal Regulation 28 C.F.R. §551.20, the Bureau of Prisons must provide “medical and social services related to birth control, pregnancy, child placement, and abortion.”

A comprehensive, sortable table of these summaries (including links to relevant statutes) can be accessed here.

Additional Federal Laws for Reference:

The Hyde Amendment (1994) stipulates that federal funds cannot be used to cover the cost of abortion except in instances of rape, incest, or life endangerment of the pregnant person. Consequently, the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) does not pay for abortions (except in these aforementioned circumstances) for incarcerated people in federal facilities (8,10,11).

Moreover, incarcerated people are ineligible for Medicaid coverage because of the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP) under Section 1905(a) of the Social Security Act (1965) (1o,12). When MIEP was first drafted, the “predominantly adult male prison population was already ineligible” for Medicaid.12 By contrast, today nearly two million people are incarcerated, with rates of female incarceration skyrocketing in recent decades (13). MIEP was never a just policy, but is having progressively more severe consequences as the prison population grows. By contrast, today nearly two million people are incarcerated, with rates of female incarceration skyrocketing in recent decades (12,13). MIEP was never an equitable or just policy, but is having progressively more severe consequences as the prison population grows (12).

Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (PREA) requires that incarcerated people who are raped while in custody receive “timely and comprehensive information about all lawful pregnancy-related medical services” though abortion is not named explicitly, and in practice information does not always translate to tangible access.

Barriers to Abortion Care in Carceral Settings:

In their epidemiologic surveillance study of 22 state prison systems, all FOB sites, and six county jails, Sufrin and colleagues found “discrepancies between abortions requested and abortions received” and reported “the abortion ratio of 1.4% in study prisons was 13 times lower than the U.S. ratio of 18%” (8). Prison policies and practices may not always reflect state laws. Additionally, incarcerated people seeking abortions face the following barriers to care:

Financial Burdens and Insurance Gaps:

The average cost of an abortion is between $580 and $2000 dollars depending on the person’s point of gestation (14) On average incarcerated people make between $0.14 and $1.41 per hour (15).

As stated, the Hyde Amendment stipulates that federal funds cannot be used to cover the cost of abortion care except in cases of life endangerment to the pregnant person, incest, or rape (8,11).

Additionally, Medicaid programs suspend or terminate coverage when someone is incarcerated. The Prison Policy Initiative reports that within state prisons, most people were either uninsured or covered by Medicaid before being incarcerated (10). Although incarcerated people do not have access to Medicaid, Sufrin and colleagues found that some facilities covered the cost of abortion. They also found a correlation between states where Medicaid covers abortion outside of carceral settings, and states where carceral facilities assist with the cost of abortion care for incarcerated people (8).

Restrictions on Abortion:

Even in states where abortion is legal, incarcerated people may face formidable barriers to care. Restrictions on abortion care can be exceptionally difficult for incarcerated people to circumvent.16 Mandated waiting periods, multi-day appointments, scripted phone calls, parental notification laws for minors, and traveling long distances limit an incarcerated person’s access. Incarcerated people must rely on carceral staff to make these arrangements, which may lead to additional delays, if not outright refusals, in care (3,4,5,8). Additionally, even in states where abortion is legal, prisons and jails may have formal policies or informal practices that contradict state law.

Policy Gaps:

Alongside financial and logistical constraints, without state laws or formal policies in carceral settings, incarcerated people have limited assurances for abortion access. Sufrin and colleagues (2021) write: “Without access formally documented in policy protocols, people needing abortions are subject to the discretion of carceral administrators and staff” (8). In an increasingly tenuous landscape for abortion in the U.S., these gaps make incarcerated people particularly vulnerable to abortion hostility.

Recommendations:

Post-Roe, states are positioned to protect (or severely restrict) abortion access. Although incarcerated people are especially oppressed by restrictions on essential reproductive health services, the following recommendations can help to alleviate some of these harms:

- Ensure that prison and jail policies comply with state laws on abortion access and that there are mechanisms to ensure that policies are followed.

- Recognize that unnecessary restrictions on abortion, including mandated waiting periods, parental involvement for minors, and physician-only restrictions, unduly burden marginalized groups including incarcerated people.

- Expand Medicaid eligibility to include incarcerated people.

- Require that facilities provide funding and transportation for incarcerated people who need an abortion after being raped while in custody.

As stated, these recommendations are intended to mitigate some of the immediate barriers to abortion care for incarcerated people, but carceral settings are ill-equipped to meet the complex sexual and reproductive health needs of people and their families. Wherever and whenever possible, alternatives to incarceration are better suited to promote maternal, child, and family health.

Key Conclusions:

Abortion access has always been tenuous for incarcerated people. Even under Roe, incarcerated people faced formidable barriers in seeking abortion care. After the Dobbs decision to overturn Roe, incarcerated people in many states lost the few legally protected choices they had. Very few states have laws dedicated towards affirming incarcerated people’s right to abortion, leaving them particularly burdened by laws with restrictive or conditional access.

Suggested Citation:

Laine, R., Benning, S., Shlafer, R., & Sufrin, C. (2023). Abortion Access for Incarcerated People in the U.S. Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health, University of Minnesota.

Designed by Cassie Mohawk, The Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health (mch@umn.edu).

Acknowledgements:

Funding for this effort was provided by the Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health at the University of Minnesota. The Center is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number T76MC00005-67-00 for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health in the amount of $1,750,000. This information or content and conclusions of related outreach products are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 U.S. 19-1392 (2022). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf

- Nash, E. & Guarnieri, I. (2023, January 10). Six months post-Roe, 24 US states have banned abortion or are likely to do so: A roundup. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/2023/01/six-months-post-roe-24-us-states-have-banned-abortion-or-are-likely-do-so-roundup

- McCoy, E.F. & Gulaid, A. (2022, May 6). What research tells us about abortion access for incarcerated people. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/what-research-tells-us-about-abortion-access-incarcerated-people

- Graf, C. (2022, August 22). Policies to roll back abortion rights will hit incarcerated people particularly hard. KFF Health News. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/abortion-rights-policies-incarcerated-prison-jail/

- Yang, M. (2022, October 21). Abortion bans create ‘insurmountable barriers’ for incarcerated women in US. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/oct/21/us-abortion-bans-insurmountable-barriers-incarcerated-women

- Kasdan D. Abortion access for incarcerated women: are correctional health practices in conflict with constitutional standards. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009 Mar;41(1):59-62. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-2393.2009.04115909.x. PMID: 19291130

- Sharfstein, J. (2022, September 21). Jailed and pregnant: What the Roe repeal means for incarcerated people. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2022/abortion-care-for-incarcerated-people-after-dobbs#:~:text=People%20who%20are%20in%20federal,pregnant%20people%20can%20access%20abortion.

- Sufrin, C., Jones, R. K., Beal, L., Mosher, W. D., & Bell, S. (2021). Abortion Access for Incarcerated People: Incidence of Abortion and Policies at U.S. Prisons and Jails. Obstetrics and gynecology, 138(3), 330–337. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004497

- Sussman, A.L. (2022, October). Incarcerated and pregnant in post-Roe America. Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health. https://magazine.jhsph.edu/2022/incarcerated-and-pregnant-post-roe-america

- Widra, E. (2022, November 8). Why states should change Medicaid rules to cover people leaving prison. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/11/28/medicaid/#:~:text=This%20policy%20leaves%20state%20and,terminated%20when%20someone%20is%20incarcerated

- Sufrin, C. (2016, September 30). Behind more than just bars: Incarcerated women and the Hyde Amendment. Rewire News Group. https://rewirenewsgroup.com/2016/09/30/behind-just-bars-incarcerated-women-hyde-amendment/

- Edmonds, M. (2021). The Reincorporation of Prisoners into the Body Politic: Eliminating the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, 28(3), 279.

- Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2023, March 14). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2023. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#:~:text=Together%2C%20these%20systems%20hold%20almost,centers%2C%20state%20psychiatric%20hospitals%2C%20and

- Attia. (2022, April 19). How much does an abortion cost? Planned Parenthood. https://www.plannedparenthood.org/blog/how-much-does-an-abortion-cost

- Sawyer, W. (2017, April 10). How much do incarcerated people earn in each state? Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/10/wages/

- Quandt, K.R. & Wang, L. (2021, December 8). Recent studies shed light on what reproductive “choice” looks like in prisons and jails. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/12/08/reproductive_choice/