A State Policy Brief from the National JIWC

March 2023

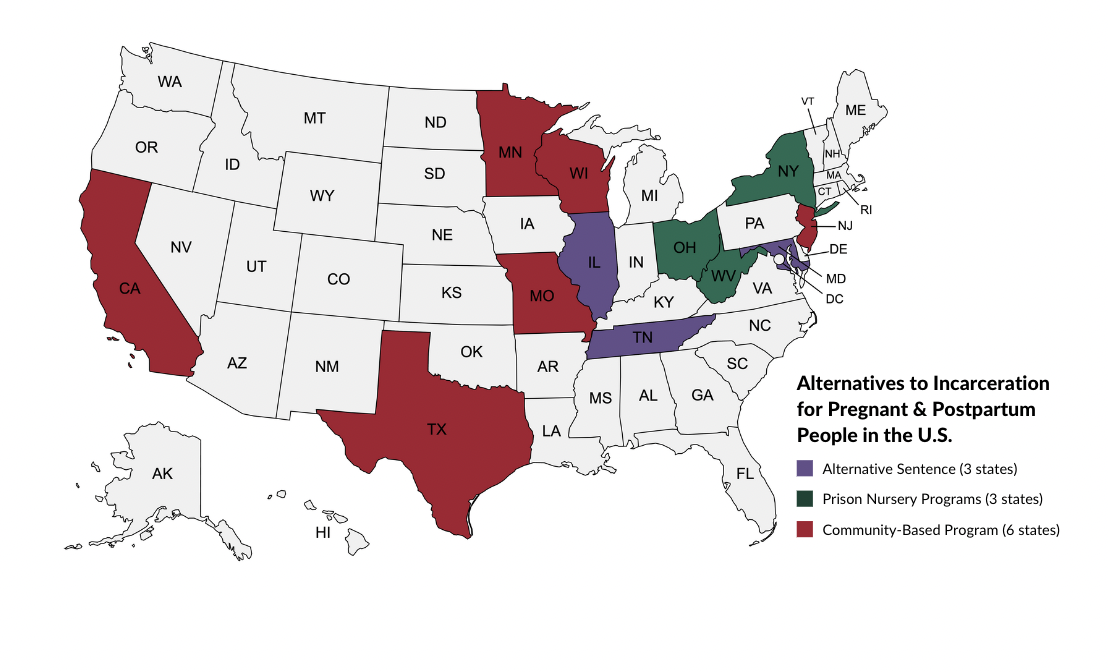

Executive Summary: Only 12 states have laws providing alternatives to incarceration for pregnant and postpartum people. Among the state laws, there is variability in terms of who is eligible to participate, what services are offered, when the intervention takes place (from pre-trial to post-sentencing), and whether or not the state laws prevent the separation of the biological mother from their newborn.

Background:

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world with rates of reproductive-aged women in prisons and jails skyrocketing in recent decades.1,2 For incarcerated pregnant people, birth is typically followed by near immediate separation from their newborn.3,4 This practice, while deeply traumatic, has long been standard practice in carceral settings.

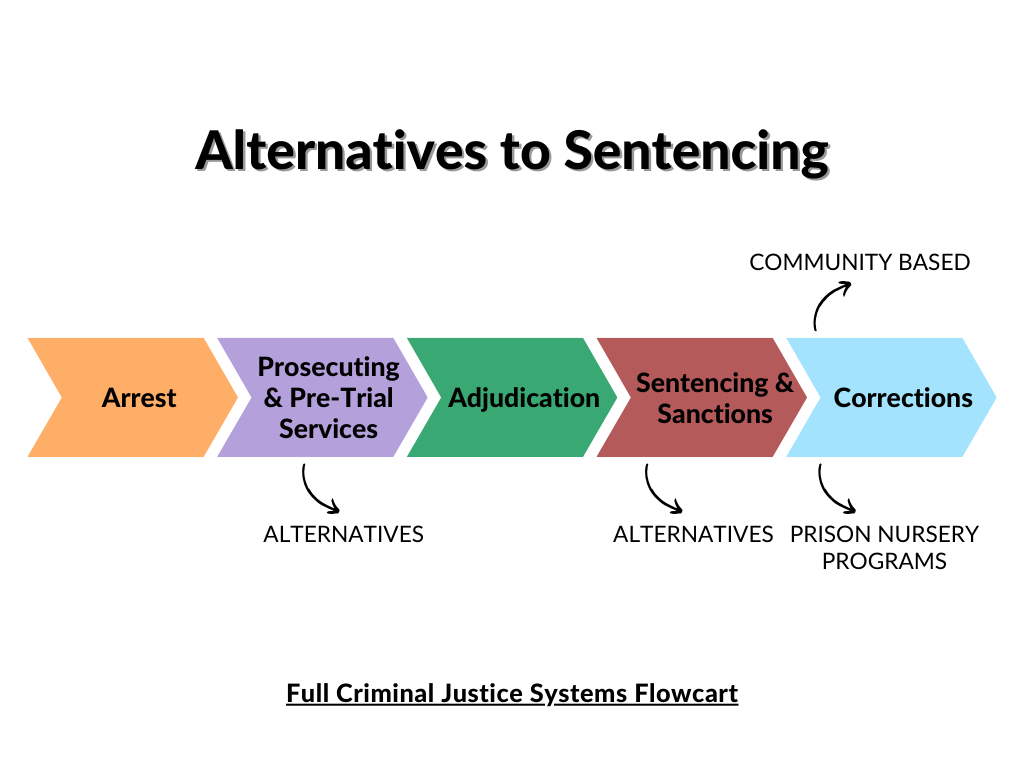

Some states have since developed alternatives to incarceration to better address the complex needs of pregnant and postpartum people and their families. Alternatives to incarceration can occur at various points in the criminal legal system, including pre-trial diversion (where an individual may be offered programs and services in lieu of a prison sentence) or post-conviction programs (where one may serve a sentence in an alternative setting).5 Sometimes these programs permit biological mothers to live with their babies, avoiding separation from their newborn at a critical period in the life-course.

While limited, evidence suggests that these types of policies and programs reduce intergenerational trauma, improve maternal self-image, promote secure attachment, encourage sustained breastfeeding, and may reduce rates of recidivism.6,7,8,9 Critics of prison nursery programs have argued that carceral settings are inappropriate for newborns and that families’ needs would be better served outside of the prison setting.10 Given these considerations, some states have implemented community-based alternatives which permit postpartum people to reside with their babies in community settings. Policies and programs specific to pregnancy vary by state, and are outlined in greater detail below.

Summary of State Laws:

Twelve states have laws related to sentencing alternatives or programs specifically for pregnant and/or postpartum people.

- 3 states—Illinois, Maryland, and Tennessee—have laws that allow permanent or temporary alternative sentences to be granted for pregnant people or for women with young children.

- 3 states—New York, Ohio, and West Virginia—have laws that create or authorize prison nursery programs. These laws allow infants to reside with their biological mothers at the prison, thereby preventing the separation of mother and baby that would otherwise occur. Several other states (e.g., Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Washington) have prison nursery programs, though they are not codified in legislation.11, 12

- 6 states—California, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, Texas, and Wisconsin—have laws regarding community-based programs for pregnant and/or postpartum people to reside outside of prisons and jails with their babies after birth. Other states (e.g., Alabama, Illinois, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Vermont) have community-based programs, though they are not legislatively mandated.13

A Closer Look:

Pre-Trial Alternative Sentencing:

Most states intervene after the pregnant or postpartum person has been sentenced to prison; however, Illinois allows for electronic home monitoring as a condition of pretrial release to reduce the number of pregnant people held in jail. Tennessee’s law grants a short, temporary furlough of up to 6 months to a pregnant person to permit childbirth and bonding between the mother and child in the community. In Maryland, the Governor can exercise executive clemency and grant a pregnant person parole, a reduced length of sentence, or an alternative residential setting for pregnancy; however, after birth, they are to be returned to a facility as soon as their health allows.

Community Based Programs:

Minnesota’s law permits the Commissioner of Corrections to identify alternative community-based options for pregnant and postpartum people. In Wisconsin, the Department of Corrections partners with local nonprofits to provide similar non-restrictive programming and support to pregnant and/or postpartum people. Texas allows postpartum people to live with their newborn in a community-based setting where they have access to additional resources. California, Missouri, New Jersey, and the federal Bureau of Prisons focus specifically on providing substance use treatment to pregnant people and parents.

Prison Nursery Programs:

In New York, West Virginia, and Ohio state laws permit a postpartum person to return to a correctional facility with their newborn. Some prison nursery programs require that participants comply with certain requirements, including education and counseling, in order to remain eligible.

| Type | State |

| Alternative Sentence (3 states) Have laws that allow permanent or temporary alternative sentences to be granted for pregnant people or for women with young children. | Illinois Maryland Tennessee |

| Prison Nursery Programs (3 states) Have laws that create or authorize prison nursery programs that allow infants to reside with their biological mother at the facility, thereby preventing the separation of mother and baby that would otherwise occur. | New York Ohio West Virginia |

| Community-Based Programs (6 States) Have laws that create or authorize community-based alternatives that allow infants to reside with their biological mother outside of prisons and jails, thereby preventing the separation of mother and baby that would otherwise occur. | California Minnesota Missouri New Jersey Texas Wisconsin |

Eligibility Requirements:

Some states base eligibility for participation in alternatives to incarceration on the length of a person’s sentence: in Ohio and California, for example, participants must have a sentence of less than 3 years. Illinois and New Jersey limit eligibility to pregnant individuals. In some states, eligibility requirements are based on the age of an incarcerated person’s child: in Tennessee, a person’s child must be under six months of age, in Minnesota and Wisconsin under one year; in California under six years; in Missouri under twelve years. Some states condition eligibility on the type of offense or length of sentence. For example, Missouri specifies that only pregnant people or parents with drug-related offenses may participate. Many states stipulate that participants are serving for non-violent crimes and have no history of child abuse.

Funding Mechanisms:

Only half of the state laws identified in our search—California, Missouri, Ohio, and West Virginia—identify funding sources for these programs; even fewer states require legislative oversight or reporting. In one exception, Minnesota requires annual reports to the legislature about participation through the Healthy Start Act. The federal Grants for Family-Based Substance Abuse Treatment authorizes appropriations of $10 million for each fiscal year 2019 through 2023 for grants to states, local governments, territories, nonprofit organizations, and Indian Tribes for residential and prison-based family substance use treatment programs for pregnant women or parents of minor children who are incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses.

Recommendations:

States have the opportunity to address the unique needs of incarcerated pregnant and postpartum people–and their infants–by enacting or expanding laws for alternative sentencing and programming.

- Consider multiple alternative sentencing and program options that intervene at different points in the criminal justice process—ranging from arrest to post-conviction and/or reentry to the community.

- Provide family-based substance use treatment and mental health support to incarcerated pregnant people and parents.

- Include mechanisms for funding, evaluation, and enforcement to help ensure that policies are effective and translate to improved practice.

Conclusion:

Historically the experiences of pregnant and postpartum people in carceral settings has been largely under-researched. Consequently, policies and programs to support this population have been inadequate. While additional research is needed to identify which alternative policies and programs are most effective, there is ample evidence demonstrating that immediate separation following birth is harmful to mothers and their infants and should not be standard practice.

Pregnant and postpartum people and their babies are at a critical stage in the lifecourse; prisons and jails are ill-equipped to meet their complex needs. Alternatives to incarceration–like alternative sentencing, prison nursery programs, and community-based alternatives–can be meaningful and impactful interventions, especially when paired with expanded health access, family-based substance use treatment, mental health support, and resources like education and vocational training.

Currently, only 12 states have written policies outlining alternatives to incarceration for pregnant and postpartum people and their infants. These states should serve as models for other states to better serve justice-involved families.

Suggested Citation:

Laine, R., Saunders, J., Benning, S., & Shlafer, R. (2023). Alternatives to Incarceration for Pregnant and Postpartum People: A Summary of State and Federal Laws. Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health, University of Minnesota.

Designed by Cassie Mohawk, The Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health (mch@umn.edu).

Acknowledgements:

Funding for this effort was provided by the Center for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health at the University of Minnesota. The Center is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number T76MC00005-67-00 for Leadership Education in Maternal and Child Public Health in the amount of $1,750,000. This information or content and conclusions of related outreach products are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Sawyer, W. (2018, January 9). The gender divide: Tracking women’s state prison growth. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/women_overtime.html

- The Sentencing Project. (2022, May 12). Incarcerated women and girls. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.sentencingproject.org/fact-sheet/incarcerated-women-and-girls/

- Sawyer, W., Bertram, W. (2022, May 4). Prisons and jails will separate millions of mothers from their children in 2022. Prison Policy Initiative. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/05/04/mothers_day/

- ACOG (2021, July). Reproductive health care for incarcerated pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant Individuals: Committee opinion. Retrieved Feburary 20, 2023, from https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2021/07/reproductive-health-care-for-incarcerated-pregnant-postpartum-and-nonpregnant-individuals

- Connecticut General Assembly (2004, September 22). Pre-trial diversion & alternative sanctions: Legislative program review & investigations committee. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.cga.ct.gov/2004/pridata/Studies/Alternative_Sanctions_Briefing.htm

- Johnson, A. (n.d.) The benefits of prison nursery programs: Spreading awareness to correctional administrators through informative conferences and nursery program site visits. Accessed January 30, 2022. https://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal/past-issues/issue-9/johnson/

- Goshin, L., Byrne, M., & Henninger, A. (2014). Recidivism after Release from a Prison Nursery Program. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 31(2), 109-117.

- National Women’s Law Center. (2010, October). Mothers behind bars. Retrieved February 20, 2023. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/mothersbehindbars2010.pdf

- Dodson, K., Cabage, L., & McMillan, S. (2019). Mothering Behind Bars: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Prison Nursery Programs on Recidivism Reduction. The Prison Journal (Philadelphia, Pa.), 99(5), 572-592.

- Campbell, J., & Carlson, J. (2012). Correctional Administrators’ Perceptions of Prison Nurseries. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(8), 1063-1074.

- Most Policy Initiative. (2021, August). Prison nursery programs. Retrieved February 20, 2023. https://mostpolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Prison_Nursery_Programs.pdf

- Deboer, H. (2012, March 30). Prison nursery programs in other states. Retrieved February 20, 2023. https://www.cga.ct.gov/2012/rpt/2012-R-0157.htm

- Women’s Prison Association. (2009, May). Mothers, infants, and imprisonment: A national look at prison nurseries and community-based alternatives. Retrieved February 20, 2023. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/publications/womens-prison-assoc-report-on-prison-nurseries-and-community-alternatives-2009/

Questions:

Contact jiwc @ umn.edu